Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/PSU/L. Townsley et al; Optical: UKIRT; Infrared: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Galileo Galilei, Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, and Edwin Hubble. World renown scientists who advanced the field of astronomy and physics during their lifetimes.

Copernicus first proposed the solar system was heliocentric rather than geocentric, Galileo created the optical telescope, Kepler discovered the three laws of planetary motion, and Hubble proved the existence of other galaxies outside the Milky Way. As diverse as their achievements are, there is one other common link between them aside from their scientific research.

They are all men.

Where were the women?

Henrietta Leavitt, Williamina Fleming, Annie Cannon, and Cecilia Payne. Perhaps these names sound vaguely familiar. Yet these were female astronomers who, just like their male contemporaries, profoundly transformed how we see the universe.

Skill did not limit a woman’s ability to perform scientific research, but archaic traditions which often restrained them from the right to decent wages and access to formal education.

Women had to overcome societal barriers to conduct scientific research. Caroline Herschel was one of the first to do so in the field of astronomy. While assisting her brother, William Herschel, she proved her ability to research as thoroughly as her male counterparts of the 19th century. She was the first woman to discover a comet.

Many women could not break free from the expectations of household work. Until the 20th century, daughters were expected to marry, not go to school. Combined with patronization and low wages, the social norms expected of women made it nearly impossible to pursue independent scientific research.

The first female astronomers fortunate enough to conduct research often struggled to receive credit for their work.

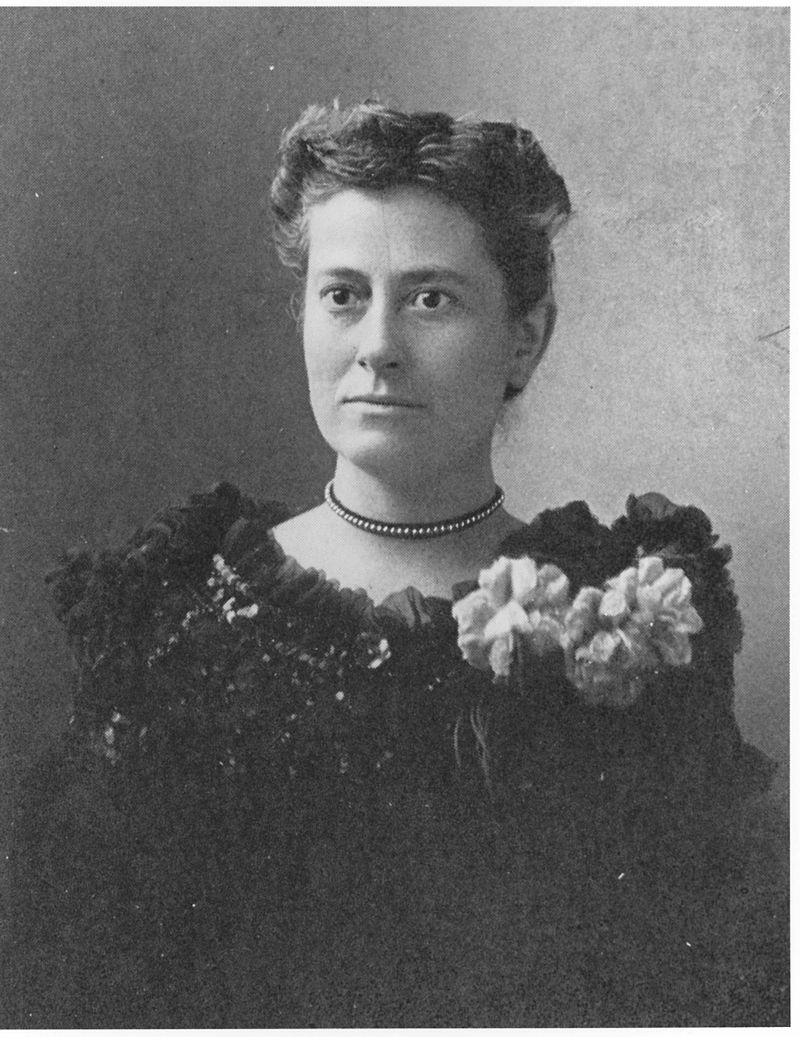

Henrietta Leavitt

(1868-1921)

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts as the daughter of a Congregational minister, Henrietta Leavitt went on to attend Oberlin College and the Society for Collegiate Instruction of Women (now Radcliffe College). She had just begun to pursue astronomy during her senior year in 1892 when she was forced to spend several years at home due to a severe illness. She recovered, but lost her hearing afterwards.

Starting in 1895, she volunteered at the Harvard College Observatory. Henrietta worked with other women, referred to as “computers”. They collected and analyzed empirical data from the stars.

While studying and recording more than 2,400 variable stars, Henrietta discovered a relationship between the time it took the star’s brightness to fluctuate and its actual luminosity.

Henrietta studied a class of stars called Cepheid’s, a type of variable star with rapid changes in brightness. Henrietta determined that the Cepheid’s fluctuation in brightness is inversely proportionate to its magnitude. In other words, the larger the star, the slower its bright-dim cycle. From this she developed the stellar relationship, known as the Cepheid variable period luminosity. She later derived a period-luminosity ratio which applied to all Cepheid stars, equipping astronomers to calculate the distance between Earth and visible Cepheid stars.

Edward Pickering was the head astronomer at the Harvard College Observatory who recruited Henrietta to his team of female computers. Despite Henrietta’s profound accomplishments, he did not allow her to further pursue her advancements. Pickering would not allow one of his computers to stray from his assigned research.

Only after seven years of volunteering did Pickering hire her at 30 cents per hour, an income equivalent to a mere $7.98 today. She passed away at age fifty-three to cancer.

A colleague remembered Henrietta as, “possessing the best mind at the Observatory”.

Courtesy Curator of Astronomical Photographs at Harvard College Observatory.

Williamina Fleming

(1857-1911)

Originally from Scotland, Williamina Fleming traveled to the United States in 1878. Her husband abandoned her during pregnancy, forcing Fleming to find work to support her son. She found work with Edward Pickering as a maid. In 1881, he hired her as a full-time computer at the Harvard College Observatory.

Fleming examined spectra, the breakdown of a star’s wavelengths of light, captured on photographic plates.

Unlike the colored lines of today’s spectra, Fleming examined plates with grayscale lines. She developed one of the first systems to classify stars into 22 groups based on their spectral lines, known as the “Pickering-Fleming System”. Using her system, Fleming cataloged more than 10,000 stars within nine years. She went on to discover the existence of white dwarfs, as well as 10 novae, 52 nebulae, and 310 variable stars.

Fleming received considerable recognition for her efforts in the astronomical community. In 1906, the Royal Astronomical Society elected Fleming into the organization, making her the first American female member.

Annie Cannon

(1863-1941)

Born in Delaware, as a young girl Annie Cannon’s mother taught her the constellations. Her interest in astronomy grew, and Cannon studied physics and astronomy at Wellesley College. After graduating in 1884, she attended Radcliffe College for two years.

At the Harvard College Observatory, Cannon joined the team of computers.

Cannon studied the spectral signatures of stars in the southern hemisphere. While trying to classify them, she realized that certain subtle characteristics of the star’s signatures did not match any of the classes within the Pickering-Fleming System. In order to classify her stellar signatures, Cannon combined, refined, and simplified the Pickering-Fleming System and another one developed by Antonia Maury.

She organized stars into spectral classes O, B, A, F, G, K, and M. These were later interpreted as the decreasing surface temperatures of the stars.

Within one minute, Cannon could classify up to three stars. In total, Cannon classified nearly a quarter of a million stars (225,000) due to her remarkable speed and accuracy.

Her remarkable work was published over the course of nine volumes in the Henry Draper Catalogue. Cannon became the first woman to hold an officer position in the American Astronomical Society. She was also the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford.

Just a year after her retirement, Annie Cannon passed away in 1941.

Cecilia Payne

(1900-1979)

Born in England, Cecilia Payne studied at Cambridge University.

During one of the public observation nights at the Cambridge Observatory, Payne asked so many questions. that someone fetched Professor Eddington in order to answer all of her questions. Eddington recommended a series of books after learning she hoped to become an astronomer. To his surprise, Payne had already read them all. Seeing her talent, Eddington allowed Payne access to the latest astronomical journals at the Observatory’s library.

After realizing that England only recognized female astronomers as worthy of a teaching position, Payne immigrated to the United States in 1923 with hopes to pursue her own research.

Harlow Shapley, Edward Pickering’s successor at the Harvard College Observatory, offered Payne a graduate fellowship. Like many of the Observatory’s computers, Payne studied the absorption lines of stellar spectra, except she applied her knowledge of the newly emerging field of quantum physics to spectra.

She understood that the linear patterns of spectra were determined by the configuration of an atom’s electrons. Payne also knew that at extremely high temperatures, one or more electrons is stripped from atoms, forming ions.

Using this knowledge, Payne concluded that stars were primarily composed of mostly hydrogen and helium with small percentages of heavier elements. Astronomers previously thought that stars were primarily composed of heavy earth elements.

Payne published her discovery as her senior thesis, which Harlow Shapley sent her thesis to Professor Henry Russell at Princeton University. Payne’s discovery completed contradicted Russell’s theory of stellar compositions. He theorized that if the Earth’s crust, primarily composed of heavy elements, were heated to the Sun’s temperature, its spectra would match that of the Sun.

Incredulous that his theory could be proven wrong, Russell deemed Payne’s conclusion “clearly impossible”.

Not to be dissuaded by Russell’s disapproval, Payne went on to publish the thesis in her book, Stellar Atmospheres. Her findings were eventually well-received by astronomers.

After completing her Ph.D., Payne lectured, advised students, and further conducted research at the Harvard College Observatory. Although these duties should have earned her the title of professor, Payne’s status remained a “technical assistant” to Harlow Shapley.

Only in 1956 did she finally received the title as a full-time professor and chair of the Astronomy Department. Payne was the first woman to earn both. Ironically, she went on to win the Henry Norris Russell Prize in 1976.

Published by Julia Mariani

Sources:

https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/201501/physicshistory.cfm

http://www.biography.com/people/annie-jump-cannon-9236960#creating-a-spectral-classification-system

http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/ww/fleming.html

http://www.space.com/17439-caroline-herschel.html

https://www.sdsc.edu/ScienceWomen/cannon.html

http://www.nls.uk/learning-zone/science-and-technology/women-scientists/williamina-fleming

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/baleav.html

http://www.famousscientists.org/henrietta-swan-leavitt/