Microbes could survive Mars’ thin atmosphere, according to recent research led by astrobiologist Rebecca Mickol at the Arkansas Center for Space and Planetary Sciences at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville.

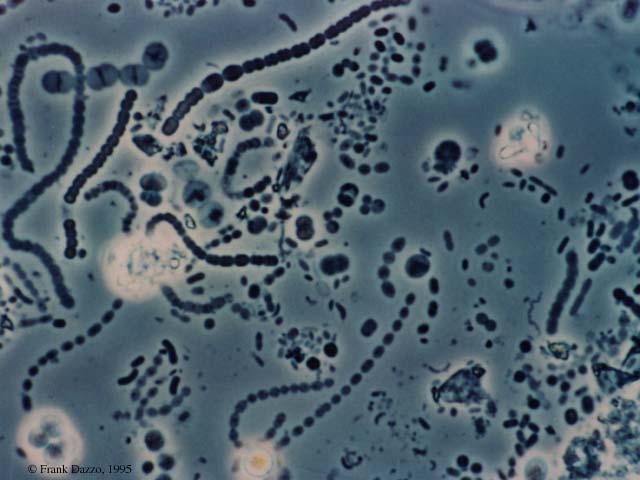

As the oldest form of life on Earth and the smallest, microbes are resilient. Fossils prove microbes existed more than 3.5 billions years ago, before the dinosaurs, a time when Earth was covered in boiling hot oceans. Microbes are unicellular organism, and they are everywhere: on your computer, clothes, and even throughout the interior and exterior of your body!

With the ability to survive billions of years on Earth, it is possible these tiny organisms could withstand Mars’ extremely low pressures, absence of oxygen, and thin atmosphere.

Evidence suggest bodies of water such as rivers, lakes, and seas covered Mars billions of years ago, mirroring the conditions where microbes thrived during the early years of Earth’s biological diversification. Perhaps life developed in these conditions on Mars and traces still remain today.

A specific type of microbe could explain the presence of methane, the simplest organic molecule, on Mars. Although there are other abiotic methods of producing methane like volcanic activity, methanogens, microbes that are known to produce methane on Earth, could equally be responsible for the presence of methane.

Methanogens do not require oxygen to survive. They often utilize hydrogen for energy and carbon dioxide for the carbon atoms used to create the organic molecules. Methanogens’ ability to survive without oxygen or photosynthesis, the process of utilizing sunlight to produce sugar, means they could survive underneath the surface of Mars. This would shield them from the planet’s harmful ultraviolet radiation caused by the absence of a protective magnetic field.

Rebecca Mickol’s team conducted experiments to observe whether or not methanogens could theoretically survive Martian conditions. The data showed that these microbes could survive from 3 to 21 days at pressures as low as six-thousandths the surface pressure of Earth, the equivalence of Mars’ atmospheric pressure.

The researchers’ next steps are to test whether methanogens could survive the extreme Martian temperatures, ranging from as cold as -100 degrees Celsius (-212 degrees Fahrenheit) to as warm as above freezing. They must also investigate if methanogens can grow and actively produce methane under such conditions.

The results of this research do not prove whether or not life exists on Mars. They will add weight to support the theory of the presence of methanogens. It is impossible to know certainly if they exist unless samples of the Martian surface exhibited evidence of microbes.

Published by Julia Mariani

(Sources: Space.com, NASA)